Throughout his career Leonardo Da Vinci painted just four female portraits, or at least that we are aware of today. The first was in c.1474, a portrait of Florentine aristocrat, Ginevra de’ Benci and the last is arguably the most famous painting in the world (Mona Lisa, c.1504). Between those dates there were two others, a painting of an unknown woman which now hangs in the Louvre – this painting was created c.1490 and is commonly referred to as “La Belle Ferronniere” (remember this name, it will crop up shortly). The final painting in Leonardo’s quartet is a portrait of Cecilia Gallerani or as it is better known “Lady with an Ermine” (see image above).

The Lady with an Ermine is a fantastic piece which demonstrates many of the qualities of the Italian renaissance as well as Leonardo’s mastery of them but for me, the most alluring quality is it’s mystery. I remember the first time I saw it and thinking to myself “Who is that lady”, “What is she holding” and “Why does she live in Poland” – I had so many questions about the painting that I felt compelled to find out more and even to the point where it was a mini obsession that I had to see it face to face.

In November 2014, I travelled to Krakow through work. During my stay, I visited Wawel Royal Castle in order to see the masterpiece – the painting has always interested me greatly so when I got the chance to see it up close, I did not let it escape. Needless to say it was no disappointment and in this post I will be taking a closer look at the painting and it’s history

Overview

Name: Lady with an Ermine

Artist: Leonardo Da Vinci (1452 – 1519)

Date Painted: c.1490

Period: High Renaissance

Dimensions: 54 cm (h) x 39 cm (w)

Medium / Material: Oil on Wooden Panel

Location: Czartoryski Museum, Krakow – Currently on display at Wawel Royal Castle, Krakow due to renovation work at the museum

Other: There has been much debate as to the identity of the woman in this painting and the symbolism of the Ermine. After many years of theories and discussion it is widely accepted to be Cecilia Gallerani, the most noted mistress of Ludovico Sforza (Duke of Milan from 1489 – 1500)

Introduction to Lady with an Ermine

Leonardo Da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine was painted in approximately 1490 – I have not seen any concrete evidence to reinforce this claim but as we shall see shortly there are specific events in history which suggests this to be accurate. Unfortunately there is very little account of the painting’s history until it was brought to Poland by Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski in approximately 1800 (image below)

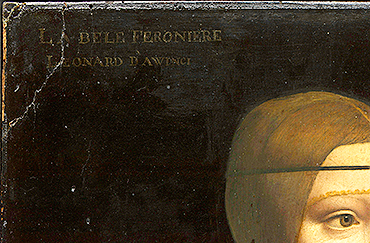

The painting quickly transferred to the Prince’s mother, Izabela Czartoryska who put it on public display at Pulawy in 1801. In 1809, the Gothic House was opened and the Lady with an Ermine was placed in the Green Room. There is an interesting story surrounding the painting and it’s identification on arrival to Poland… If you take a close look at the top left hand corner of the painting you will see the following text “LA BELE FERONIERE / LEONARD D’AWINCI (see image below)

This text is not the original work of Leonardo but was added later. La Belle Ferronniere (literal transaltion is beautiful wife of the wrought-iron craftsman) was reported to be the mistress of Francis I (King of France 1515 – 1547) and is the subject of another Leonardo Da Vinci portrait which now resides in the Louvre Museum, Paris. I would not say that the two paintings are by any means identical but when you have no internet and very little else to go on, it may have seemed logical at the time to think that they were of the same person (we will see shortly that the lady is in fact, Cecilia Gallerani). The second part of the added text “LEONARD D’WINCI” carries a little irony with it…there is no “V” in the polish alphabet and it only really appears in “foreign” spellings – it seems that when branding their painting, the new owners have adopted Leonardo as a Polish national. If the art lover in you feels outraged that someone would dare tamper with a Leonardo original then I can sympathise with you but it does get worse – forensic inspection has revealed that the original background was bluish-grey. It was over-painted black in the early 19th century allegedly by Eugene Delacroix for unknown reasons.

The lady in the portrait is widely accepted to be Cecilia Gallerani (1473 – 1536). A quick search on internet will tell you that Cecilia Gallerani was the official mistress of Ludovico Sforza and that she is the Lady with an Ermine but sources suggest that she was much more. Famed for her intelligence, literary skills, poetry and beauty, Cecilia Gallerani was born in to a large family of reasonable social standing – her father, Fazio Gallerani held multiple posts at the Milanese court and her mother, Margherita Busti was daughter to a doctor of law.

History suggests that Cecilia arrived at the Milanese court at the age of 16, having previously been betrothed to Stefano Visconti – this union was never realised but to even be considered for marriage to a Visconti is evidence that her family’s social status in Milan was doing OK. There is little evidence to suggest how Cecilia first met Ludovico Sforza but what we do know is that the relationship between the two flourished. When Ludovico Sforza met Cecilia he was already betrothed to Beatrice d’Este. He is known to have postponed the wedding several times in 1490 due to his blossoming relationship with Cecilia. The marriage finally took place in January, 1491 but may have been slightly soured by the fact that Cecilia was carrying Ludovico’s child. Cecilia would give birth to a son named Cesare in May 1941 and remain at court for several months to follow – I can only judge this on today’s standards but I think it is fair to say that this would have made life pretty difficult for the Duke of Milan. Perhaps it was pressure from Beatrice or her family but Cecilia was finally removed from court and married to Ludovico Carminati dé Brambilla – they lived at the palace of Carmagnola which was a gift from Ludovico to his son.

Following the death of Cecilia there is little record of the painting until it arrived in Poland. As we move on from this point with the Lady with an Ermine, we can see how ingrained the subject of war is and how it has dictated it’s movements throughout Europe. The year 1830 marked the Polish-Russian war know as the Cadet revolution or “November Uprising”. In order to protect the painting, it was evacuated to Paris and kept in the Hotel Lambert. The Lady remained in France until the 1880s – the Franco-Prussian war forced the move back to Krakow in 1882 where the painting would eventually go on display as the main attraction of the Czartoryski museum (opened in 1876).

The next chapter in the painting’s history is the Great War (1914-1918), once again the painting was evacuated for it’s safety to the Gemaldgalerie, Dresden – The painting returned safely in 1920. Perhaps the most interesting event in the history of The Lady with an Ermine was during the second world war (1939-1945). In 1939, the painting was stolen during the Nazi occupation of Poland. During his regime, Adolf Hitler initiated what is now referred to as the Nazi Plunder – Famous works of art from all across Europe were stolen with the intention to display them at the Fuhrermuseum in Linz, Austria (Hitler’s never realised, monumental museum of art). Along with works from Rembrandt and Raphael, The Lady was taken from Poland before returning to Wawel castle in 1940 under the care of Hans Frank (Governor General of Occupied Poland). Following the end of the war in 1945, the painting was again taken out of Poland only to be found in Bavaria (Frank’s villa in Fischhausen am Schliersee near Nauhaus) by a team of allied troops dedicated to art retrieval – this group retrieved many priceless works of art at the end of World War II and were known as “The Monuments Men” (Check out the 2014 film starring Matt Damon and George Clooney, it is the account of the Monuments Men and just remember that The Lady with an Ermine was one of the masterpieces to return home – many works of art sadly did not return home and searches remain to this very day). Following the spoils of war and its heroic return to Poland, movements have since been restricted to exhibition duties such as the “Leonardo…Painter at the court of Milan”, National Gallery (2011 – 2012) and the occasional move due to renovation works.

Now that we have a brief idea about the history of the painting, we can move on to look at some of the more aesthetic elements of the painting

Style and Inspiration

The Lady with an Ermine is painted using oils on wooden panel (walnut). Oils were introduced to Italy in approximately 1470 so it is fair to say that it was a relatively modern medium. Oil painting is believed to have been established throughout Northern Europe in the 15th century under notable figures such as Jan Van Eyck. As a pioneer of revolutionary techniques and ideas, it is no real surprise that Leonardo Da Vinci quickly took to oils. It was this mindset which caused Leonardo to experiment with new methods for his famed masterpiece “The Last Supper” in order to achieve greater vibrancy. His choice to paint the wall dry opposed to traditional fresco has led to its much hastened deterioration. Leonardo would go to use oils on many of his future works including La Gioconda (Mona Lisa).

Leonardo Da Vinci exercises masterful application of a technique called Chiaroscuro in many of his works and this is no exception – Chiaroscuro greatly contrasts light and dark to achieve the feeling of volume and depth. The right hand of Cecilia and the coat of the ermine demonstrate this technique well and it is clear to see its effectiveness – the subtle changes around the neckline also appear to provide depth and amplify the contours of the form. The use of light and dark along with subtle mid range tones brings a real feeling of life to the painting and when viewing it face to face, it truly felt like Cecilia Gallerani was in the room with me.

The subject of patronage is immensely important when discussing the famous works of the Italian Renaissance – many people, including non art lovers would be able to tell you that Leonardo Da Vinci is the genius behind the Lady with an Ermine and The Last Supper but few would be able to tell you that Ludovico Sforza commissioned them both. The truth of the matter is that equally to Leonardo, without Ludovico Sforza, we would not have the Lady with an Ermine or even the Last Supper. The inspiration behind the painting is the relationship between Ludovico and Cecillia but the context or circumstances of the painting remain unclear. There is evidence that Isabella d’Este, sister of Beatrice and one of the leading ladies of the Renaissance requested to loan the painting in a letter to Cecillia in 1498, a year after the death of Beatrice. Maybe uncertain, but this may indicate that the painting was given to Cecillia as a gift from Ludovico as she still maintained possession following her move to Carmabnola.

At the beginning of this post I mentioned three distinct questions “Who is that lady?, What is she holding? and why does she live in Poland?” So far we have discussed Cecillia Gallerani and touched upon the events which brought her to Poland. Now it is time to address what Cecillia is holding and arguably the main focal point of the painting – before I begin writing about famout paintings, I like to show them to my family and particularly my sons Alex (4) and Oliver (6). The reason I do this is to ultimately expose them to a little culture but mainly that I love to hear their comments. The first thing Alex said when seeing the Lady with an Ermine was “what is wrong with that cat?” and Oliver agreed that the “Ferret looked funny” – although slightly off target, both confirmed that the Ermine was the main point of interest. The “cat” or “ferret” is in fact an Ermine, as the name of the painting confirms but please be aware that this may bot have been the name which Leonardo gave to the painting. We will see the connections to the Ermine shortly but there are earlier drawings by Leonardo entitled “Study of an Ermine” baring resemblance to help support this.

The Ermine is a member of the weasel family and more commonly is the name given to a stoat or short tailed weasel whilst wearing it’s winter white coat (yes, they change from brown to white between seasons). As a symbol of purity, it is said that an Ermine would rather face death than soil its white coat – this would have provided a fitting symbolic reference to the beauty and purity of Cecilia Gallerani. It is all so a belief that the Ermine was symbolic of pregnancy and provided protection to expecting mothers – this ties in with the fact that Cecilia gave birth to Cesare (Ludovico’s son) and supports the claim that the painting was completed c.1490. This may also suggest that the painting was commissioned as a gift upon the news that Cecilia was expecting (complete hearsay on my part, but just a theory :). The symbolism of the Ermine continues to resonate with Cecilia through her surname. In 1907 it was noted by A.E Hewitt that the Greek word for ermine is galee which happens to be the first part of her surname (Gallerani) – a clever reference which was undoubtedly intentional from one of the brightest minds throughout history. Moving on from Cecilia there are also strong connections between Ludovico Sforza and the ermine. Ludovico was a member of the Order of the Ermine, a chivalric order from the Duchy of Brittany in the 14th & 15th century – this honour was bestowed on him by Ferdinand I, King of Naples in 1488 and would be his personal emblem thereafter.

The inclusion of the Ermine within the painting certainly ticks all of the boxes for Leonardo, it will please his patron whilst paying appropriate compliment to his mistress – it is common to see elements of a painting which are specifically included to please the person who is paying for it, Leonardo had a good relationship with Ludovico but was probably aware that his reputation was only as strong as his latest work. This is common for artists of the Renaissance who were working for extremely powerful men, there is no better example of this than in the compliments paid to the Medici by Sandro Botticelli in Primavera.

Composition

The composition of the Lady with an Ermine is relatively simple whilst at the same time being quite revolutionary. Portraiture in the 15th century tended to follow a certain pattern. Whilst it may have been common for portraits to be be drawn in the 3/4 (three quarter) it is unusual for the head to be turned in the opposite way – by doing this Leonardo has brought a dynamic quality to the painting as if Cecilia has suddenly turned around to look at something or someone (obviously Ludovico) that has caught her attention. It is also interesting that both Cecilia and the Ermine appear to be focussing on the same thing. In 1493, Bernardo Bellincioni wrote the following sonnet which has captured the expression of the painting quite beautifully

Why are you angry? Whom do you envy, Nature?

Vinci, who has portrayed one of your stars;

Cecilia, now so beautiful, is she

Whose lovely eyes cast the sun into dim Shadow

The honour is yours, though in his painting

He’s made her seem to listen, but not to speak.

Think how very alive and beautiful it will be

-To your greater glory – for all time.

Therefore you may now thank Ludovico.

And the genius of Leonardo

Who want her to belong to posterity.

He who sees her thus, even though too late

To see her alive, will say: this is enough for us.

Now to understand nature and art.

The placement of the ermine may also carry symbolic reference to the relationship of Ludovico and Cecilia. Cecilia is demonstrating an extremely gentle touch over her ermine and it is hard to describe her affection towards it as anything other than loving – no doubt this would have been pleasing to Ludovico to see his mistress caring so much for his emblem and ultimately his soon to be born son, Cesare.

Many of the works to have emerged from Renaissance Italy paid particular attention to geographical surroundings and placement. As we look at the painting we can clearly see that the light source is emerging from the right hand side of the painting. The left side is almost submerged in to total darkness. It is fair to assume that the painting was intended to be displayed in a room which allowed light in from the right hand side, maybe through a window or door and viewed slightly from below. These aspects of the painting clearly demonstrate Leonardo’s masterful ability to capture light within his paintings. When I travelled to Krakow to see the painting, the exhibition room was cast in almost complete darkness – true to form, there was a single light source from the right hand side which gave life to the painting, I was lucky enough to be in the room alone and at one point felt like I had been transported back through time to view this masterpiece – only the blinking light from the security camera was spoiling the illusion.

As you look at the painting you are drawn to the face of Cecilia and then quickly to the ermine. From there your eyes begin to wander as you spiral up and down the painting. The lines of the arms and the ripples in the Cecilia’s clothing force you in different directions whilst ensuring that you take a curved route back to the hands, face and ermine.

It is difficult to completely interpret the painting without seeing it in its original condition – the background was originally blue-grey and may have provided further insight on how to understand the painting better

Conservation

The painting has been subject to multiple forensic examinations and restoration. The first in 1955 under the guidance of Rudolf Kozlowski at the Warsaw Laboratories and notably in 1992 under David Bull at the Washington National Gallery Laboratories where it also underwent restoration. The examinations concluded that the painting was carried out on a piece of walnut measuring between 4 and 5 millimetres in thickness. A layer of brown under-paint cast upon a layer of gesso (white paint mixture commonly used to prepare surfaces for painting)

The forensic inspections have concluded through X-ray techniques that Leonardo used charcoal to prick the preparatory drawing, a technique which is commonly used in Frescos. Even more interesting is that fingerprints of Leonardo were found within the surfaces of the paint. Much scepticism surrounds the works of Leonardo so this would have been a huge relief for the owners to have this confirmed

Further inspection to the under-drawings indicates that there may have been a window or door present in the original composition. This was removed by Leonardo and it did not make in to the final version. Studies led by Pascal Cotte have literally cast new light on the painting. Using a highly advanced technique known as Layer Amplification Method (LAM) he was able to examine successive paint layers and decompose brush strokes. This study provided an insight in to the working mind of Lonardo and that the painting was in fact completed in several stages – firstly without the Ermine, secondly with a smaller ermine before arriving at the final iteration.

My trip to Krakow

I could not complete this post without documenting my trip to see the painting face to face and sharing a few photos.

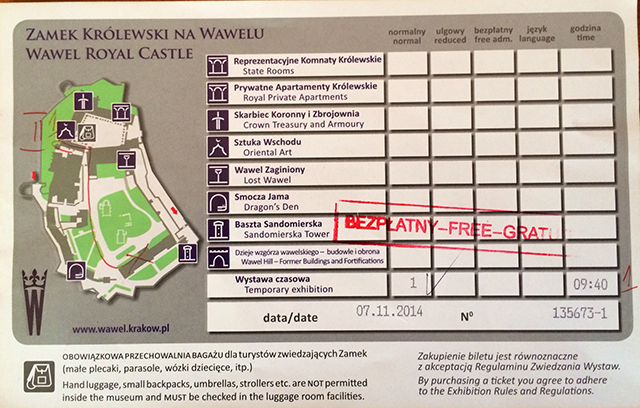

On the 7th Novmber 2014, I went to see the painting whilst it was residing at Wawel Royal Castle, Krakow. It was an early start and I got to the castle about 09:30.

From there I went straight to the ticket desk to get my admission

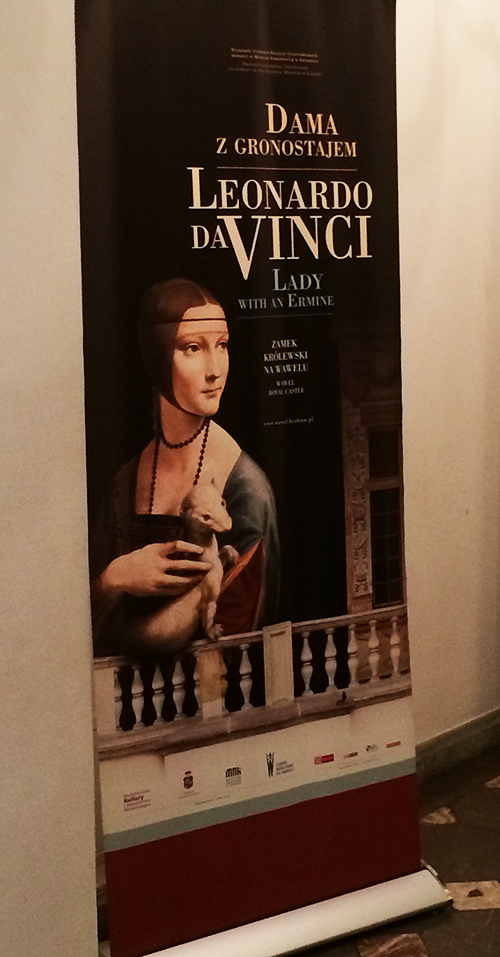

Walking towards the exhibition, I was quite excited but still able to take in the fantastic surroundings

Once I got inside the exhibition building it was a quick walk up to the second floor to see the painting. The picture below is the final point at which I was allowed to take photos. For anything further then you will need to take the trip yourself…

In short it was a fantastic experience to see this masterpiece face to face and something which I will never forget. The room was set up with all of the proper conditioning required to house a masterpiece but at the same time extremely dramatic. Almost complete darkness with a single light source, the whole painting was lifted to something which cannot be appreciated in a photo, much like seeing Vincent Van Gogh’s Sunflowers photography simply does not do it justice – sorry guys but you just need to go and see it

Final Thoughts

Firstly, thank you for taking the time to read this post. I hope you have found this page with a desire to learn more about this fantastic painting and that I have helped you in your quest. Leonardo Da Vinci was a genius of his time and one of the finest artists in history. For me it is amazing to learn more about him and to see his work face to face is always a fantastic experience. Although the history of this great painting is slightly lost and tarnished by war, its story is a journey and it’s survival in Poland is symbolic of the country’s victory against constant oppression.

The information in this post is a mixture of my own opinions along with facts I have researched from various sources.