Preceding Paradise – Ghiberti & Brunelleschi Competition Panels

Arguably one of the greatest creations in western art are the bronze doors situated at the Eastern entrance of the Florence Baptistery. Famously labelled as the “Gates of Paradise” by Michelangelo, Lorenzo Ghiberti spent 27 years perfecting his eternal masterpiece. Before Ghiberti arrived at his gates, he created his first set of doors in bronze for the North entrance of the baptistery following a competition held by the Arti di Calimala in 1401. In this post I will be taking a close look at the competition and in particular, the submissions by artistic rivals Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi.

Overview

Name: The Sacrifice of Isaac

Artist: Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378 – 1455) & Filippo Brunelleschi (1377 – 1446)

Created: circa 1401

Period: Early Renaissance

Medium / Material: Bronze Casting set within Quatrefoil

Current Location: National Museum of Bargello, Florence

Other: The two panels were entries for the competition to decide commissioning for a set of bronze doors to be housed at the Baptistery of San Giovanni, Florence. Lorenzo Ghiberti won the commission and went on to produce the bronze doors now located at the North entrance of the baptistery (1403-1424). He would later go on to create a second set of doors proclaimed as “The Gates of Paradise” by Michelangelo (1425-1452)

Introduction

In 1330, Andrea Pisano was commissioned to make a set of bronze doors for the Florentine Baptistery of San Giovanni. The commission was awarded by the guild of cloth finishers and merchants in foreign cloth (Arti di Calimala) who were charged with maintaining the baptistery in the mid twelfth century. The Pisano doors were completed in 1336 and to this day remain at the South entrance of the baptistery. 65 years later, following the catastrophic events of the Black Death in Florence, the Arti di Calimala commissioned work for the doors situated at the East entrance of the baptistery (the doors would later be moved to the North entrance to make way for the Gates of Paradise, Lorenzo Ghiberti between 1425-1452). In 1401, a competition was arranged by the guild to decide which artist would be given the great honour of creating the new bronze doors. Seven noted artists of the time (Filippo Brunellesci, Symone da Colle, Nicholò d’Areço, Jacopo Della Quercia da Siena, Francesco di Valdombrina, Nicholò Lamberti and Lorenzo Ghiberti) competed for the commission which would be presided over by a panel of 34 judges. The brief was to depict the Sacrifice of Isaac (Genesis 22) in bronze – two of the entrants excelled. The two entrants were of course, Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi. The commission was eventually awarded to Lorenzo Ghiberti but there is no doubt that Brunelleschi made it a tough decision – some accounts even exist whereby both artists were awarded the commission jointly but Brunelleschi refused to work alongside Ghiberti. The two panels have been preserved and exist to this day on display at the Bargello. We can now take a closer look at both of the panels as we explore one of the most significant events in the development of renaissance art. This competition would set in motion a chain of events which leads directly to paradise…

Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Competition Panel

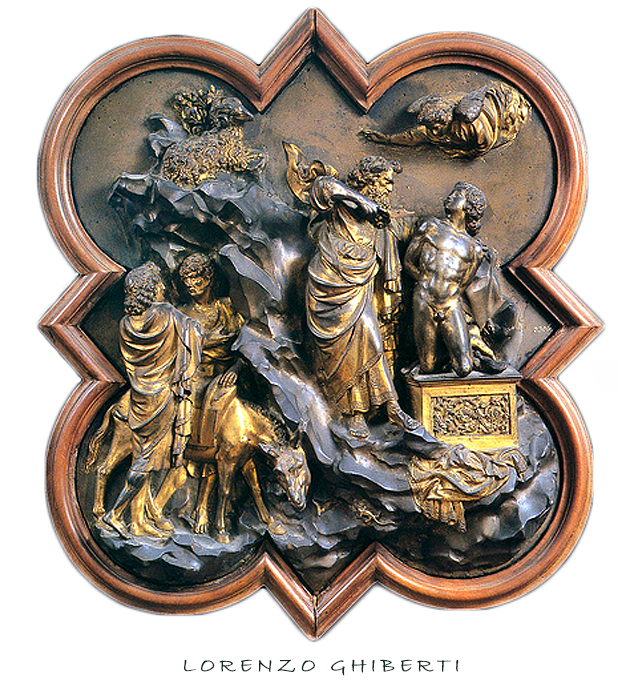

Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Competition Panel

The image above is the competition panel submitted by Lorenzo Ghiberti – there will images in this post which show each feature in greater detail but feel free to revert to this image so that you can see the panel in full.

Filippo Brunelleschi’s Competition Panel

Filippo Brunelleschi’s Competition Panel

The image above is the competition panel submitted by Filippo Brunelleschi. Throughout this post I will be making comparisons between the two panels and their detail but feel free to revert back to this image see the panel in full.

Style

Both of the competition panels are similar in style owing largely to the brief given as part of the competition. Like the panels which make up the Pisano (North) doors, each entry is cast in bronze and mounted within a Quatrefoil (See below)

In terms of artistic style we can see multiple influences. We can see the curvelinear styles (more so in the Ghiberti panel) associated with the Gothic period and we can also see celebration of the human form which is strongly linked to the Renaissance art. Many people consider the Baptistery door competition as the moment which really kick-started the Renaissance and as we look at the panels in greater detail we will discuss this.

Inspiration

The Inspiration for the two panels is The Sacrifice of Isaac. As part of the competition, the Arti di Calimala requested that the panels tell the famed story of Genesis 22 from the old testament. The following extract of Genseis 22 verses 1-13 is from the King James Bible (KJV). In order to understand the panels then it is important to digest the reference text:

1 And it came to pass after these things, that God did tempt Abraham, and said unto him, Abraham: and he said, Behold, here I am.

2 And he said, Take now thy son, thine only son Isaac, whom thou lovest, and get thee into the land of Moriah; and offer him there for a burnt offering upon one of the mountains which I will tell thee of.

3 And Abraham rose up early in the morning, and saddled his ass, and took two of his young men with him, and Isaac his son, and clave the wood for the burnt offering, and rose up, and went unto the place of which God had told him.

4 Then on the third day Abraham lifted up his eyes, and saw the place afar off.

5 And Abraham said unto his young men, Abide ye here with the ass; and I and the lad will go yonder and worship, and come again to you.

6 And Abraham took the wood of the burnt offering, and laid it upon Isaac his son; and he took the fire in his hand, and a knife; and they went both of them together.

7 And Isaac spake unto Abraham his father, and said, My father: and he said, Here am I, my son. And he said, Behold the fire and the wood: but where is the lamb for a burnt offering?

8 And Abraham said, My son, God will provide himself a lamb for a burnt offering: so they went both of them together.

9 And they came to the place which God had told him of; and Abraham built an altar there, and laid the wood in order, and bound Isaac his son, and laid him on the altar upon the wood.

10 And Abraham stretched forth his hand, and took the knife to slay his son.

11 And the angel of the Lord called unto him out of heaven, and said, Abraham, Abraham: and he said, Here am I.

12 And he said, Lay not thine hand upon the lad, neither do thou any thing unto him: for now I know that thou fearest God, seeing thou hast not withheld thy son, thine only son from me.

13 And Abraham lifted up his eyes, and looked, and behold behind him a ram caught in a thicket by his horns: and Abraham went and took the ram, and offered him up for a burnt offering in the stead of his son.

Aside from being one of the most famous stories from the bible, it would have provided the guild with a good chance to see how the entrants depicted a wide range of figures both human and animals, mountainous scenery and inanimate objects. There is also a tremendous amount of tension and emotion within the sacrifice of Isaac – once again it would have given the guild a great insight in to how the winning sculptor would undertake the awarded commission

Composition

In this section we are going to take a look at the composition of the two panels in direct comparison (feel free to revert back to the panels in full at the top of this post). Although the narrative of the panels is the same, there are significant differences – as per the biblical reference, each panel contains seven figures (Abraham, Isaac, The Angel, The Ram, The Two Servants and The Ass) and we can begin to look at them in closer detail

Abraham

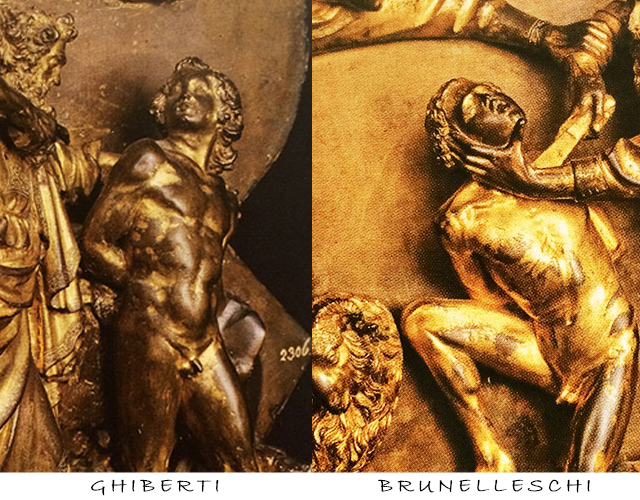

Looking at the two panels from the front it is difficult to appreciate the depth and perspective of each figure but especially Abraham as the heads are both in profile. The image above features the two versions of Abraham and allows you to see them from a different angle – it also allows you to see the faces in greater detail.

As we look at Abraham in the Ghiberti panel we can see that he has placed his left hand around the shoulder of Isaac. In his right hand he holds the knife which is aimed directly at his son. The angle of Abraham’s right arm creates a diagonal which runs parallel with the mountainous background, shoulder line of Isaac and the robes flowing behind him. This diagonal extends in to the top left quadrant of the quatrefoil and descends in to the right center with great precision – even at this early stage we can see how Ghiberti used the shape of the quatrefoil to enhance his work, a feature which is somewhat absent in the Brunelleschi panel. We can see in the image above that Abraham is looking directly at his son and you can almost see the pain in his expression due to the task he is about to perform – there is tremendous detail in the face, hair and beard and the expression of genuine anguish has been captured with outstanding effect. The body of Abraham in the Ghiberti panel exhibits the curvelinear style associated with Gothic art, his weight appears to be on his back foot as he carefully negotiates the rocky terrain whilst demonstrating lightness of touch and agility. Ghiberti’s Abraham is adorned with exquisite robes which have been sculpted with immaculate skill, his robe also seems to flow upwards over the shoulder providing a sense of motion and energy through action. The body of Ghiberti’s Abraham has been positioned in the three quarter view with the majority of his torso, waist, legs and both feet facing towards the viewer, this is quite different to the Brunelleschi panel but the heads of both Abraham’s have been positioned in the profile (side-wards on) view. Situated almost centrally on the panel, Ghiberti’s Abraham is the main focal point of the piece and clearly demonstrates Ghiberti’s grasp on human proportion, ability to create energy within his composition and skill as a true master of sculpture.

Moving on to the Brunelleschi panel we can see that Abraham has been sculpted entirely in profile and carries a presence which dominates the entire panel. If we imagine the panels as snapshots in time then it is clear that the Ghiberti panel precedes Brunelleschi’s by a few seconds, Ghiberti’s Abraham is transfixed on Isaac as he draws back his knife to deliver an almost sympathetic killing blow (if there is such a thing), there is no awareness of the angel who is yet to play a part. There is a far greater sense of urgency in the role performed by the angel in the Brunelleschi panel, Abraham is looking directly in to the eyes of the angel as he presses the knife against the throat of Isaac. Everything about Brunelleschi’s Abraham radiates strength and aggression – from the way he has grasped his son around the throat, which seems to be in direct contradiction to the caring way Ghiberti’s Abraham has taken his son around the shoulder, to the almost haunting way he is starring in to the eyes of the angel. In terms of composition, Brunelleschi’s Abraham is the centerpiece of the panel with no real consideration given to the quatrefoil surrounding. Ghiberti seems to have embraced the shape of the frame and incorporated it into his design where Brunelleschi has created a composition which just happens to sit within a quatrefoil.

There is no doubt that Brunelleschi has created his Abraham with a great deal of skill and care, the detailing of the robes, hair and facial features providing a fine example but I am not convinced by the execution of proportion in relation to the other figures in the panel. There is also the depiction of Abraham which I feel is more appropriate in the Ghiberti panel – for me, Brunelleschi’s Abraham does not radiate the same level of majesty and seems more in line with a self portrait opposed to depicting one of the bible’s most important figures

When I look at the Ghiberti panel, I see Abraham as an exceptional figure surrounded by exceptional figures…with the Brunelleschi panel, I get the feeling that we are looking at the Abraham and Angel show with everyone else merely playing a cameo role.

Isaac

Isaac is a figure which has a strong affinity with the city of Florence. In 1402, around the time of the competition, Gian Galleazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan launched an assault upon Florence – it seemed to both parties that it would only be a matter of time before Florence fell. In a dramatic change of circumstance, Gian Galleazzo was taken ill and died. It was then perceived by Florentines that god had saved Florence from certain doom, much like he did when commanding Abraham to spare Isaac.

Of all of the figures we can see in the two panels, the greatest contrast in my opinion is in the depictions of Isaac. Brunelleschi’s Isaac appears to be nothing more than a weak child who is being man handled by his father where Ghiberti’s Isaac is perfectly proportioned and radiates strength in a celebration of the human figure.

It is easy to look at Ghiberti’s Isaac and make comparisons with Michelangelo’s David – both figures are a celebration of the human form and confirm that man is indeed, the measure of all things. The Brunelleschi Isaac however forms quite an awkward figure, ill-proportioned in relation to the other figures in the panel and twisted into a pose which radiates weakness.

The Angel

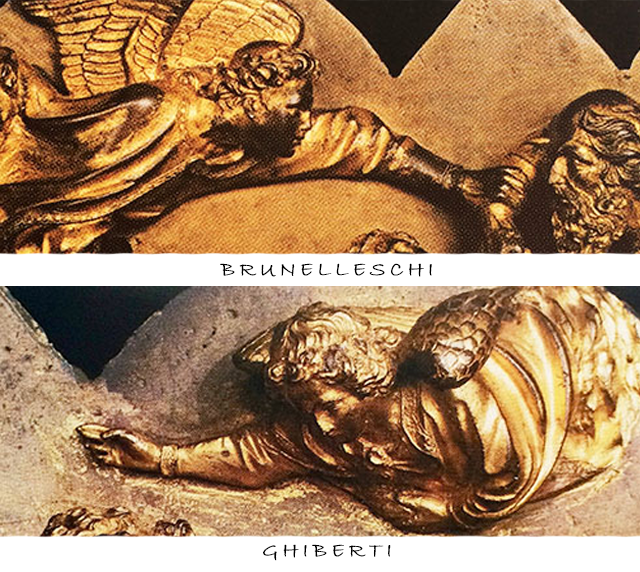

The two angels are quite similar as figures, executed with fantastic detail and tremendous craft but there is great contrast in terms of positioning. The most obvious thing when looking at Brunelleschi’s angel is that the figure seems to be entering from a level plane in relation to Abraham, considering that the angel has obviously descended from heaven, one would expect the angel to descend in to the frame as in Ghiberti’s depiction. Ghiberti has foreshortened the angel and created a diagonal which forces the viewer to move directly to Abraham and the important events unfolding at the center of the panel.

The Background

The two depictions of the mountainous surroundings are extremely different. Ghiberti has created a scene which is dominated by an exquisite rock formation and it truly feels like everything is happening high up in the mountains. Ghiberti has been very clever with the background as it takes the viewer on a journey which enters every area of the panel except the angel’s space, a feature which I believe separates the earthly world from that of the divine. If you only focus on the mountains, you will visit all of Ghiberti’s panel in a natural sweep of vision.

Moving on to Brunelleschi’s background, there is very little to talk about and you find yourself having to go looking for the mountains rather than them coming to you. What can be seen of the mountains is quite odd and ill-proportioned in relation to Abraham. Ghibertis’s panel clearly shows that the story is taking place atop of a mountain where as Brunelleschi’s just happens to have a mountain in the background

The Ram

Ghiberti Brunelleschi Ram

There are not many things which I consider to be better in the Brunelleschi panel but the figure of the Ram is one of them. The pose of the ram is more interesting and creates a sense of motion which is absent in the Ghiberti. As with the rest of the composition, the positioning of Brunelleschi’s ram is very linear with everything taking place on horizontals and verticals. The positioning of the Ghiberti Ram is enhanced by the mountainous backdrop but does seem a little static.

The two depictions of the mountainous surroundings are extremely different. Ghiberti has created a scene which is dominated by an exquisite rock formation and it truly feels like everything is happening high up in the mountains. Ghiberti has been very clever with the background as it takes the viewer on a journey which enters every area of the panel except the angel’s space, a feature which I believe separates the earthly world from that of the divine. If you only focus on the mountains, you will visit all of Ghiberti’s panel in a natural sweep of vision.

Moving on to Brunelleschi’s background, there is very little to talk about and you find yourself having to go looking for the mountains rather than them coming to you. What can be seen of the mountains is quite odd and ill-proportioned in relation to Abraham. Ghibertis’s panel clearly shows that the story is taking place atop of a mountain where as Brunelleschi’s just happens to have a mountain in the background.

The Servants and The Ass

Ghiberti Brunelleschi Servants

Both Ghiberti and Brunelleschi chose to place the three figures (two servants and the ass) at the bottom of their panels, this is no surprise as they play a somewhat cameo role in the main event. We can see from the reference text above (Genesis 22) that Abraham instructed the servants to stay at the foot of the mountain whilst he proceeded to complete his task.

Brunelleschi has again opted for a very linear style, placing all three figures on the same horizontal plane along the bottom of the panel. There is no question that Brunelleschi has depicted the servants in more complex poses which demonstrate his abilities with great effect but I feel that he has neglected the composition. The three figures at the bottom of the Brunelleschi seem to consume the entire panel with little consideration to the quatrefoil surrounding. Ghiberti however has gone for the less is more approach and worked his figures expertly in to the lower left quadrant of the quatrefoil – they are present in the scene but they do not take focus away from the main events.

And the Winner is…

Lorenzo Ghiberti was announced as the winner of the competition and commissioned by the guild to create the bronze doors. There are several accounts regarding this decision which make it quite difficult to understand the truth. In Vasari’s Lives of the artists he writes that Brunelleschi agreed that Ghiberti should have been awarded the commission solely due to the skill in his craft “Donato and Filippo, seeing the diligence that Lorenzo had used in his work, drew aside, and, conferring together, they resolved that the work should be given to Lorenzo”. The other version of events states that Brunelleschi and Ghiberti were awarded the commission jointly, but refusing to work with Ghiberti, Brunelleschi opted out of the work – there is evidence of this behaviour in the construction of the dome of the Santa Maria del Fiore. Whatever the details of this event, it does not deter from the fact that Ghiberti was the one who went on to create the bronze doors

It is suggested that one of the main reasons for Ghiberti’s triumph is that his panel was cast from a single piece of bronze, where Brunelleschi attached each of his figures to the panel. Not only was Ghiberti’s method significantly lighter, it would have been a far cheaper method due to less bronze. There are also suggestions that Ghiberti had a pretty close relationship with some of the judges throughout the production of his competition panel.

I do prefer the work of Ghiberti but that does by no means discredit the Brunelleschi panel, both are remarkable pieces of artwork and it is a testament to their quality that they have survived all of this time.

Summary

It is often stated that Italy (particularly Florence) was the cradle for the renaissance and without the support and financial backing from wealthy patrons, many of the great artists would not have been able to complete their masterpieces. This is genuinely the case with this competition and without the Arti di Calimala we would not have the Gates of Paradise, the North doors or even the two panels to appreciate. The events which unfolded during this competition is often credited as being “the beginning of the Renaissance” – there are probably too many factors contributing to agree with this fully but Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi have played their part in the history of western art and laid solid foundations for future masterpieces. The creation of Ghiberti’s panel is a seed which grew over the next 50 years in to one of the finest creations known to the man – The Gates of Paradise

Thank You for taking the time to read this post and please feel free to leave comments below

Hi, Can I use these images for classroom purposes? Thank you!

Caitlin

Hi – Of course you can